If Money Has the Power to Make One Forget Anything

On Bluebeard, Blink Twice, and It Ends With Us (Which it probably doesn't)

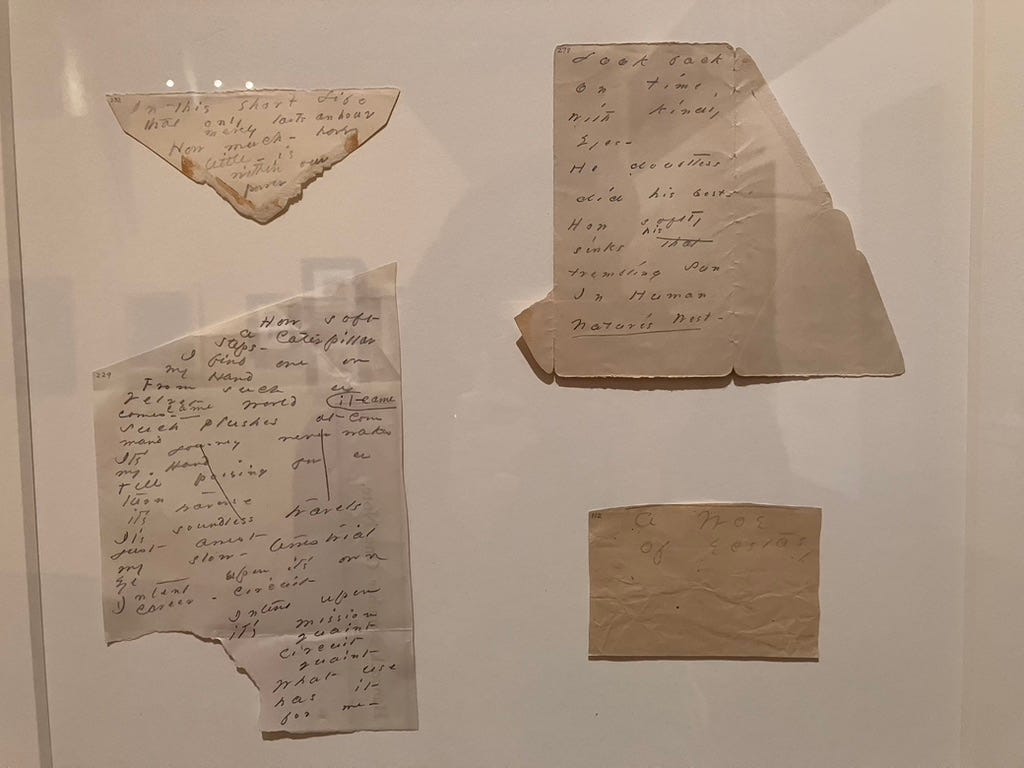

So I was driving while on Zoom, which I think might be my new MO for spring because I am classically over-committed in the kind of way that leaves me jotting small notes on envelopes like I am Emily Dickinson. Only my em dashes are more about my lack of punctuation commitment than my poetics.

In reality, I am jotting things down on envelopes (hello tax documents) and water-stained post-its because I’m writing around, edging closer to what might be the book I have wanted to write for years.

I was in a car, maybe two years ago now with a nearly retired professor of Peace Studies talking about how I am certain the suppression and flattening of the menstrual taboo from “sacred and profane” to purely “profane” has led to manifestations of mass violence, gun violence, all the television shows in which a girl dies in the first 10 minutes never to be resurrected, and of course our obsession with serial killers.

I’m not sure what the professor said, but my theory raised some questions—is there research on this? Where does this idea come from? (I heard where is your proof?) I know, I write about this a lot, but there’s a kind of somatic experience that happens when pieces of research constellate into an idea that makes sense. It might even be similar to sticking a key in a lock only to find it drips blood and all of your sisters are locked inside. There is something horrifying about discovery.

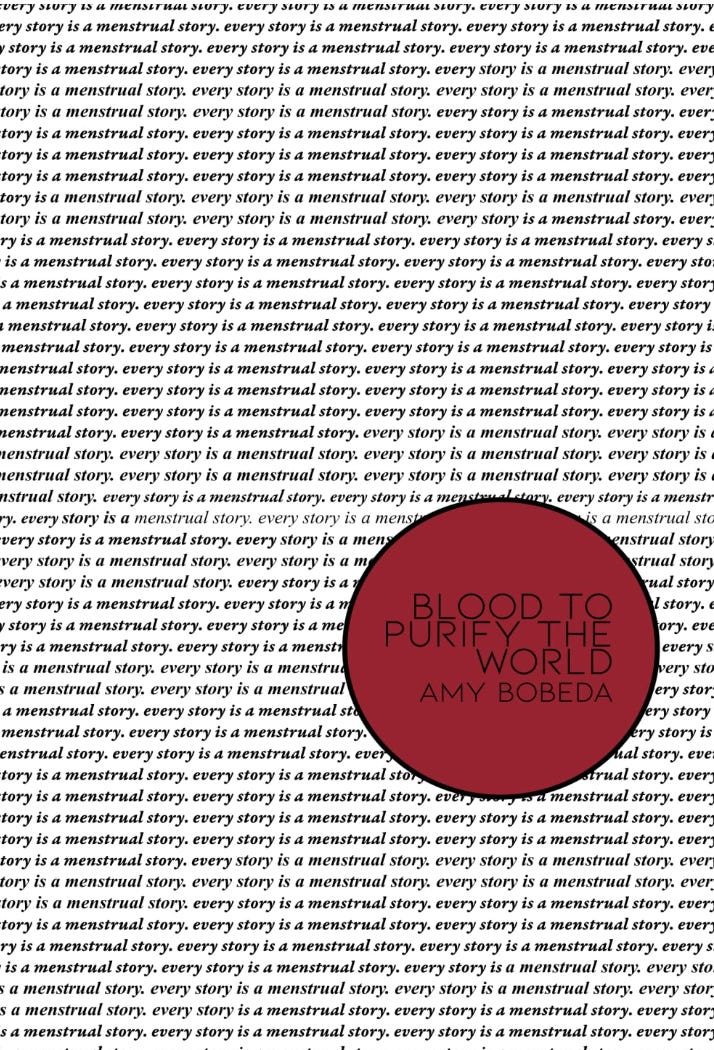

This week, my new book came out, finally, (Huzzah!) Complete with beautiful blurbs by

Helen Nde, and the fabulous poet Laura Wetherington; I have spent so much time hemming and hawing over the revisions, the political statements, and the punctuation of a book that I mostly wrote 2, 3, and even 4 years ago. Looking back at it, I’m not sure I wrote or lived much of it at all.The book was shared with friends on the Zoom call as we discussed Jung’s ideas of the animus as the inner force that helps a woman get her creativity into the world. (It’s not quite gendered this rigidly; gender is, after all a social construct.) At this moment, it struck me how I generally have little trouble letting an idea move from my body into a creative form. A professor told me this in grad school, “I suspect you have no trouble writing.” Generally, I don’t. However, when it comes to my work entering the world in the form of a book, it seems impossible. Printed. Bound. Costly on every level from paper pulping to the reader’s bank account, I don’t know what to do and in some cases, I can’t move forward, so the book goes nowhere.

I experience a similar freeze when I’m supposed to announce things to students via email. (I keep running into students saying I owe them an email which is not a reply but an email I have only written in my head but never on paper). I wait and wait and the waiting takes up so much mental space I could have just written a quick “hi please remember to bring scissors to class tomorrow, thx bye!” and moved on with my day, but something keeps me from doing this.

While driving, and listening to the discussion about the animus, I thought about Bluebeard because I probably will spend my whole life thinking about the book about Bluebeard which doesn’t exist yet. If, as Jung (or really Marie-Louise von Franz) suggests, we read every character in a fairytale as a part of the self, Bluebeard is seen as the animus. Termed as “demonic” or “possessive” he is also in some ways, cultured, secretive, and possesses riches. I want to think about riches beyond money because money is a recent invention. Instead, I want to think about riches in the reality that Bluebeard owns a home with many rooms. So many, that there is room for him to keep his secrets (all the women’s bodies) safe from view. Perhaps this also means that Bluebeard can compartmentalize. He can keep a secret, but also, some part of him doesn’t want to keep a secret, he wants to test his bride to see if she is trustworthy. It’s almost as if Bluebeard wants to form some sort of bond with his new spouse, but when the moment strikes to practice forgiveness he snaps. In a Keresan Spider Woman story with a similar structure, the husband murders his wives because they are not perfect. (You can read about this parallel in Blood to Purify the World.) Perfection is the enemy of intuition, the moon, the menstrual cycle.

Honestly, if we read the wife’s transgression of opening the forbidden door as “broken trust” rather than “transgression,” the story could develop a different resonance.

As I was driving, I saw this image of Bluebeard after his wife revealed the bloody key or poorly scrubbed egg because the blood is magic and cannot be un-blooded. And under his anger and outrage there was sadness. There was heartbreak. Anger is, after all, a secondary emotion. And it’s the one he acts on. I thought what if Bluebeard’s anger isn’t about his wife knowing the truth about him, it’s about her knowing the truth about herself?

What if he’s telling us something about reactionary behavior?

This must be why everything in my house smells like onions—I peel back and back and back and in each peel I find another fiber to strip away into another question.

Von Franz might call Bluebeard the demon animus complex that causes us to murder ourselves. But there is so much in a fairytale left unsaid because they hold archetypal patterns and behaviors. I think this means they can hold many truths at once, sometimes in contradiction. “The animus,” Jung writes, “is a psychopomp, a mediator between the conscious and the unconscious and a personification of the latter.” This means the animus acts out unconscious behavior—often in what feels like possession from “something came over me” or “I wasn’t in my right mind when I…”

So, say you were told to ignore your period 🩸; your only associations with other bleeding bodies are watching folks slide tampons up their sleeves on the way to the bathroom. Or maybe someone asks you for Midol in the college bathroom. But mostly, in a culture largely devoid of menstrual rituals, you find yourself alone in a giant house filled with whatever it is that entertains you all day. Except, there is something you do not know—something you feel like you could or must know. You get the sneaking suspicion there is something you can’t quite remember.

Since Covid, I’ve found my memory lapses. I stand in the kitchen and have no idea why. In my 20s similar behaviors occurred from Lyme Disease: finding my keys in the freezer; losing my car in the parking lot; and the unwavering inability to read. Now, however, I have an acute awareness of gaps; I can see a colander with giant holes that are empty spaces in my brain where something should be. Some days the colander disappears and my headspace is empty. How rapid the loss of memory can be.

Since watching Blink Twice, I’ve thought a lot about screen memories, gaslighting, and this misconception that the inability to remember trauma makes its effects disappear. Bessel van der Kolk and his popular book, The Body Keeps the Score, argue against this—it’s not what our mind remembers, it’s what our body does. The issues, they say, are in our tissues. This also applies to menstrual blood.

At the end of the week, I developed a sneaking suspicion that something was wrong. As if the place I have lived for three years was somehow different—I caught myself liking my apartment rather than feeling indifferent. Let me say this again—most days I feel indifferent about the spaces I occupy, and I like it. I sat in the bathtub and tried to remember if I had ever written a bad love poem for Valentine’s Day (a question posed by some graduate students). I realized I had not thought about love in years, perhaps since my obsession in graduate school with the fact that English only has one word for love, which makes us grossly misunderstand and complicate our experiences.

The next morning, I read about the Blake Lively lawsuit drama with costar Justin Baldoni, because I can’t stop thinking this must really be about the common inability of actors to distance themselves from the archetypal behavior that possesses them in a scene, or in this case an entire production process. Not consciously considered method acting, this kind of possession goes unnoted. It might even be what we call “in the zone” or “feeling the energy” while performing a creative act. The similarity between the film It Ends With Us, based on the novel about ending the cycle of abusive relationships, and the leading couple’s behavior that has led to lawsuits is too uncanny to be a coincidence. Or maybe, I’m misreading the whole thing and it’s really about power and profit.

I closed my computer, fell back asleep, and hours later bolted upright, acutely aware there was something I couldn’t remember. Days later the feeling remains—I have no idea what it is I can’t remember but I am aware that whatever it is—it isn’t okay.

This too happens in Blink Twice as the protagonist recovers her memories after drinking snake venom, the antidote to a memory-erasing flower tested on women after powerful men assault them on a billionaire’s island. The billionaire, played by Channing Tatum, sees so much potential in the power of forgetting without realizing that if the power dynamics shift, he too will be left forgetting. In forgetting, the film finds—there is not bliss.

Reviewers call the film a “Bluebeard narrative”, but Bluebeard’s women only forget in their dismemberment. This is important.

In other fairytale variants—often the ones with three grooms who turn into animals there is a chamber a man is not allowed to enter (ATU 552). This chamber houses his future bride who needs “saving”. A persona sets out to save his anima (or as Jung would say soul) from some kind of monster. This too is a menstrual metaphor, but here instead of the man holding the key, it is a menstrual witch, wizard, or ogre barring the door—it is only after the man can slay the menstrual character, free his future bride, and take over a kingdom that the story of Bluebeard can be born. Like Blink Twice, the unraveling of the narrative memories is about following the clues. It is about sensing that which you can’t quite remember.

Before Bluebeard kept secrets from his wives they kept secrets from him. Before Blink Twice begins, Tatum’s character apologizes for his behavior. Maybe before a billionaire is a billionaire they are a person. Maybe not. Before Blake sued Justin and Justin sued Blake, he had a podcast and book called Man Enough—I wonder what could make Bluebeard man-enough. In a documentary about the lawsuits, the narrator says something like—before this, no one knew Justin Baldoni’s name, now no matter what, people will remember—he will be okay. So will Blake Lively if money has the power to make one forget anything.