In class, I attempted to teach “master narratives” and “counter-narratives”. Despite several Googles and a skim of the textbook I still don’t quite understand the premise of the master narrative or why we would teach it in a composition class unless we’re looking at facts and alternative facts or decolonizing research.

There is at least one student this semester obsessed with Hamilton. Another likes to share poems like I Miss New York. This fills me with a fuzzy nostalgia. I wish I could say there was a day on which I wasn’t thinking about Hamilton or a day on which I wasn’t missing New York perhaps as a concept more than a place. Some days when I am running along the Brooklyn waterfront and it is too cold or too warm but especially when it is a little bit rainy, I think about how I will miss it, even the bodies dredged up in the East River. What can I say, I feel a little Whitmanesque sometimes—we all contain multitudes, especially when Crossing Brooklyn Ferry. Perhaps this is the master narrative of New York, The greatest city in the world, as Hamilton sings.

Sometime, around Thanksgiving, I decided I wanted to rewrite the constitutional amendments to make them about periods. This is probably thanks to the students’ outrage about arsenic tampons. It was most certainly about the election. It is in moments like this one that I hold two Diane di Prima quotes, one in each hand like little scoops ready to dip into fresh water: the greatest war is the war against the imagination, all other wars are subsumed in it; I have just realized that the stakes are / myself / I have no other / ransom money, nothing to break or barter but my life.

When Angelica Schyler sings when I meet Thomas Jefferson I’mma compel him to include women in the sequel! I think about the insignificance of an exclamation point. I think about how little that dot is, without a vertical line shooting from it: nothing more than a period. I think about how we think periods are nothing but burden and pain.

The morning class after mine is called something like Writing and the Law. It reminds me of Sabrina Orah Mark’s image of the LAW: something with teeth or something like an eraser that could rub her out with its pink nub. In fact, unlike Hamilton’s cheeky attempt to say something about women’s rights, the law has made so much progress rubbing so many people into the kind of faint marks that are just enough to distract you from the page but not enough to understand what they say. Perhaps the law has just turned bodies into ghosts.

I’m spending an unnatural amount of time in the bathtub watching television. This week, I watched Shining Vale which opens by comparing the side effects of depression medication with the side-effects of demonic possession, noting that women are more likely to be possessed by demons.

In Marie Louise von Franz’s exploration of fairytales, she looks to Bluebeard and his relatives (Silver Nose, Mr, Fox, the Fitcher, and friends) as the demonic husband or the demonic animus.

I probably think about Bluebeard as much as Hamilton; I think they are probably related. When I look into master narratives which are also sometimes called meta-narratives it is confusing because those should be two different things—the narrative of George Washington and the cherry tree comes up. In class, I say—I think the master narrative of the American Dream counts because a master narrative is this over-arching narrative that we think has some “universality”. I don’t tell them anything about Levi-Strauss’ idea of one myth only but in the same class, I say—you know the hero’s journey? Well, it was stolen from the heroine’s journey. One student grins. We’ll get back to it, hopefully. With a lovely narrative spiral or even a labyrinth made of thread.

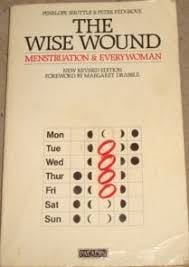

In Penelope Shuttle & Peter Redgrove’s The Wise Wound, they regard premenstrual symptoms not as merely a change in hormones or need for nutrients like potassium (though really you should take omega 3’s to reduce menstrual pain and inflammation), instead they call it a range of neglected experiences.

In a comparison of premenstrual symptoms and sleep deprivation in non-menstruators, they find the symptoms are the same. Does this mean sleep deprivation creates pre-menstrual symptoms? No. They posit it’s not sleep deprivation, it’s dream deprivation that leads the sleep-deprived folks to experience clumsiness, nervousness, bloating, or heaviness, all common experiences of the luteal phase of pre-menstruation.

Shuttle and Redgrove identify two broad types of menstruators based on their dreams: “convergers” and “divergers”. Convergers are noted as those who are good at traditional testing; divergers excel at “imaginative open-ended tests”. Convergers experience more anxiety-based dreams before menstruation while divergers experience them during mid-cycle ovulation. The pair takes this further to say that convergers are “apprehensive of menstruation while divergers are interested in what menstruation will bring but balked at the experience by society’s howlback avoidance of it.”

In Shining Vale, Courtney Cox plays a middle-aged erotica writer who has spent the last decade attempting to write her next book. Her family has just moved to a haunted house in Connecticut because she slept with the handyman her husband hired to fix a faucet in their tiny Brooklyn apartment. Stuck alone in the attic-turned-office, she develops a relationship with Rosemary, one of the house’s ghosts who can’t wait to write a thrilling smutty novel together. This, of course, can only happen when Rosemary is taken into Cox’s body possessing her and slowly overpowering her behaviors and decisions. Von Franz would probably call this a shadow possession.

By the second season, Rosemary appears as the very alive neighbor who brews a special tea that brings back Cox’s period. We’re not talking about a flash period, we are talking about a full-blown cycle that even leads to a pregnancy. For a few days, my computer glitches on the scene in which Cox is told “a monthly visit” is worth it if the tea also reverses gray hair.

The show oscillates between what might be a dream, what might be a reality, and what most of the time someone in the series terms as psychosis. Time is marked by supertitles that tell us what day it is or how many weeks have passed because time melts away from the narrative.

In their dream studies Shuttle and Redgrove reference, ovulatory dreams that feature babies, eggs, gems, and jewels. The studies, however, tracked very few menstrual dreams.

Premenstrual dreams featured blood images and religious symbols the dreamer could understand as the arrival of death and resurrection. One dreamer saw a girl whose head was cut off and then reattached—“Something has given this woman permission or confidence to approach her period so that she is no longer afraid of the threshold of blood, that her dream sees it as a renewal. The next stage would be a conversation with this dream figure,” Shuttle and Redgrove write.

In class, I ask students to write to their own Bluebeard’s. They are kind and generous and don’t have much to say. Some even thank their Bluebeards and I can’t help but wonder if we are ignoring something more important or if maybe we haven’t met Bluebeard at all. In both Shining Vale and Bluebeard a woman is trapped, upholding the status quo—wife, mother, homemaker in a giant old house of ghosts, but in both cases, this woman is curious and questioning. She does not trust others’ commands like “Don’t go in the basement”. Instead, she follows what she senses, even if the curiosity kills her.

In the Fitcher’s Bird, the girl is tasked with carrying an egg, a little like the antiquated tradition of carrying a bag of flour. “Preserve the egg carefully for me,” Fitcher says, “and carry it continually about with thee, for a great misfortune would arise for the loss of it.” It doesn’t take much nuance to catch the ovulatory moment, quickly followed by dropping the egg into a vat of blood in the room full of all the other wives’ (and the women’s sisters’) body parts.

The thing about Bluebeard, the demonic animus is that he can be integrated, like any other part of the psyche. The question is, what is it that leads to this “demonic” possession? When I good the “negative animus” a psychologist writes about “the raging bitch.” To me, this seems like a little bit of cultural construction and a whole lot of menstrual supression.

In The Wise Wound, Shuttle and Regrove theorize about the violent nature of pre-menstrual and menstrual dreams. Is it the taboo attitude towards the period that manifests violence? Is master narrative perpetuated by all the Bluebeard iterations overpowering the imagination until we all become Convergers, afraid of what the menstrual dreams will bring? Shuttle and Redgrove note that anyone can become a Diverger—ready to open the locked door the period’s unconscious. Perhaps the diverger knows, the stakes are truly themselves. Perhaps they can uncover the narrative before the “master narrative” until the haunted basement is no more—until they are no longer afraid of their dreams.